Starting work on a new piece always brings a level of anxiety. Will this work? And collaborating with a new person brings additional questioning: How will we get along? Who will do what? With Louis it was hard to pin down a specific schedule of when he would be there and so I learned quickly that I would need to have a whole lot of flexibility on one hand and at the same time a sense of stability for the six performers.

Usually I had to rent rehearsal space for the company. For this piece I didn’t, as Louis generously made a studio available for us at Henry Street. That also gave Louis the flexibility of making himself available as his schedule allowed without having to do any additional traveling.

I remember climbing stairs to a lovely small dance studio, like an attic area of Henry Street, that worked perfectly for us, especially at first when we were working in small groups and not running the full piece. I quickly learned that having a high degree of flexibility was almost an understatement, and I had to be prepared to choreograph or rehearse whether Louis was there or not. Louis and I had talked about the fact I should feel free to choreograph sections of the poem that appealed to me. Quite a few early rehearsals were with Kezia, Loretta and Deborah creating movement to sections of the poem in my typical modern dance style.

When Louis was available, I knew my role was to watch carefully what he was setting so that I could review and rehearse sections he set, at later rehearsals when he wasn’t there. Louis is a true showman, looking for dramatic opportunities. He soon framed the piece with entrances that each dancer invented, crossing the stage while shouting “Let My People Go.” This is followed by a confrontation of the three women that then leads to Kezia’s being pushed to the ground. In the silence that follows, Deborah moves downstage, and picks up a stage prop book of the James Weldon Johnson poem and begins to read from it. I loved watching Louis work and build amazing dramatic moments into the thirty-five minute piece. He found moments to add comedy and surprise twists to the retelling of the poem, and to bring in recent history with references to Martin Luther King and South Africa.

One of the memorable moments of the rehearsal period was when Mark Childs came to his first rehearsal with Louis. Louis assigned him some movement to do, and Mark strongly proclaimed he didn’t dance; he was there to chant. Louis would hear nothing of it and gave him a movement assignment, and before long, Mark was totally engaged in not only singing but in dancing. And then Louis wanted to know what instrument Mark played. When Mark said he played a saxophone, he was told to bring it to the next rehearsal. And so Mark brought his sax to rehearsal. When Louis suggested that Mark slide across the stage while playing his saxophone, Mark drew the line and refused. Louis respected that and so at three different places in the piece Mark added variety by playing both traditional melodies on the sax and improvising while crossing or circling the stage. And so it went . . . Louis’s imagination challenging performers and adding fun theatrical moments. Louis asked Kezia what tricks she could do. Stumped, she said she didn’t do any tricks. Laughing, she added, “I blow bubbles,” referring to children’s soap bubbles that she had brought on a recent tour. And so there is Kezia in the piece, running across the stage waving a child’s bubble wand with a stream of bubbles floating behind her (“Pharoah called for his magic men, and they worked wonders, too”).

At another moment, Loretta breaks into a rap version of “Let My People Go.” At one of our meetings in Louis’s office before rehearsal he shared that he loved to listen to pop music that kids were listening to, so that he stayed in touch with current trends and had new things to inspire him. I loved his sense of “entertainment” and saw that even in dealing with difficult and serious subjects, playful movement worked. I was learning a lot from him.

Loretta had appeared in the Broadway show “Purlie” that Louis had choreographed, and at one rehearsal Louis added a step from that choreography. Loretta carefully coached the other dancers – including Mark — so that the movement and accent would be just right. Loretta was invaluable in helping us when Louis wasn’t there, as she understood his style and what he would want.

Following a dance solo for Rob, Louis added the moment that had sparked his interest in doing the project. Loretta sang the spiritual “Go Down Moses” while Mark chanted the related Hebrew text from Exodus while circling the stage. That remains for me one of the most powerful moments in the thirty-five minute piece.

As we got close to the final rehearsal, our drummer, Leopoldo, joined us, and Louis came up with the idea of the drummer opening the show, entering an empty, dimly lit stage or walking down the aisle to the performing area. The show also ended with just the drummer on stage and one dancer having been pushed to the floor. It worked. We began to have run-throughs and always some new idea came to Louis’s imagination and he eagerly added it. I remember sitting beside him at our final rehearsal which was in a much larger room than usual, and thinking how well the overall piece looked. My husband Murray joined me, since I wanted to make sure he would get to see it and to meet Louis. I was amazed at the new ideas and changes that Louis continued to add, even at that final rehearsal. That was nearly 30 years ago, yet the experience is strongly etched in my mind.

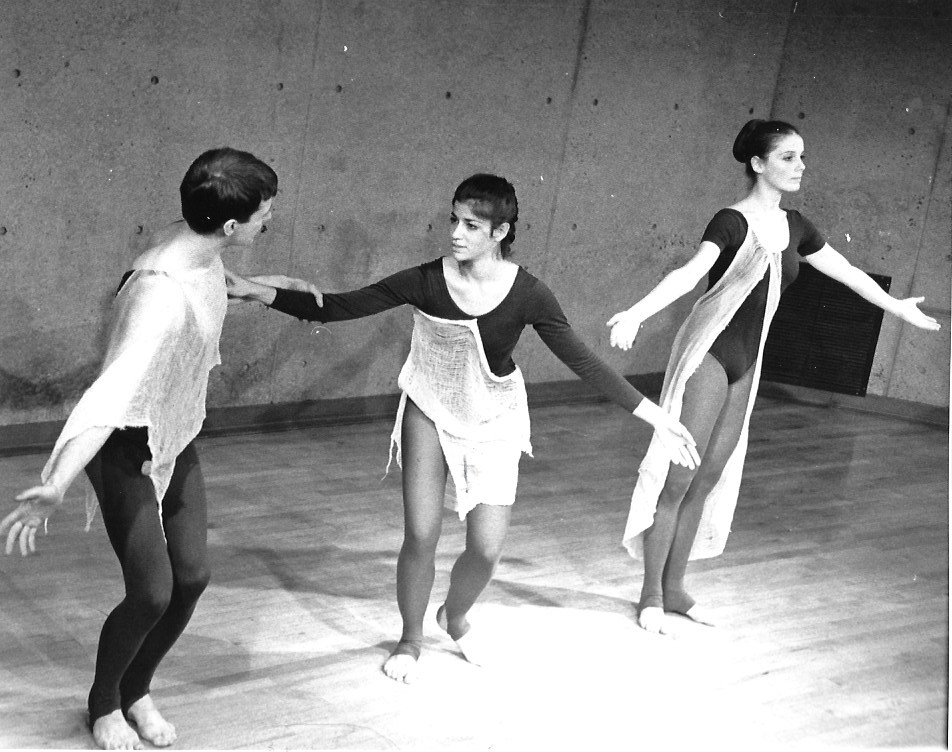

I am so glad that we had photographer Tom Brazil come to one of the rehearsals and capture the early stages of the piece. Later he returned and took pictures at a performance.

Rehearsing the “Purlie” step. From L to R: Loretta Abbott, Rob Danforth and Deborah Hanna.

“And Moses with his rod in hand.” From L to R: Deborah, Loretta, and Kezia

“And Pharaoh called the overseers!” From L to R: Rob, Mark, Deborah and Loretta

All three photos by Tom Brazil

Print This Post

Print This Post

Recent Blogs

- The Pioneers of Modern Dance: My Firsthand Experience

- A Visit to a Costa Rican Art Museum Triggers a Fascination with Mascaradas

- Thoughts after Streaming a Memorial for Dance Critic Jack Anderson

- Keeping Up With What is Happening in the Dance World

- A Sijo Poem for the Winter Solstice

- Episode 33: The Universal Dancer Podcast – I’m Interviewed by Leslie Zehr

- The National Symphony of Costa Rica

- Can you go home again?

- Odd Thing to Find on eBay

- Chopping in the Kitchen