The grant from the Nathan Cummings Foundation underwrote four one-week residencies at four contrasting sites. Our first residency was held from February 25 through March 3 in Wilmington, Delaware. Plans called for us to work with the community on many levels. Workshops were held for schoolchildren as well as adults, and community members participated in two performances – one at Temple Beth Emeth (as part of the Friday night Sabbath service) and the other at the Episcopal Church of Saint Andrews and Matthew (SAMS). (As mentioned in previous blogs, Canon Lloyd Casson of SAMS, a longtime supporter of Avodah, was instrumental in the development of the Forgiveness Project.)

One of the requirements of the grant was to have good documentation of the residencies. A budget had been built into the grant to cover the cost of having two former members of the Avodah Dance Ensemble observe and take notes of what they saw. Kezia Gleckman Hayman and Beth Millstein were super at doing this and I was thrilled when Kezia mentioned that she still had her notes about how we integrated community members into the performance.

The following description is from Kezia’s report about Congregation Beth Emeth, Wilmington, DE (March 1, 2002):

I first observed the community members in a 6 p.m. rehearsal for the 8 p.m. temple service that evening. All four participants had attended at least one workshop with the company during the preceding days. Now the participants were to be incorporated into the performance piece with the company, using movement phrases they were about to create, themselves, based on workshop activities.

JoAnne began by brainstorming responses to ”Forgiveness is… “ The group chose three images it wanted to use in this performance: “liberating a closed heart,” “transformation,” and “letting go.” The ideas were translated into movement through sculpting. (One participant assumed a position expressing the given idea, and then other participants, one at a time, added to the sculpture.) This became the opening of the piece, before the entry of the company dancers.

One of the participants mentioned that she had particularly liked a workshop movement exercise in which Tucker had two lines of participants approaching each other . . . Tucker built the next section on variations of “approaching,” assigning participants to interact with the company dancers. Again drawing on images that had emerged during the workshops, one group approached as if to say “sorry,” another with the idea of returning, and the third incorporating a gesture of one’s face buried in one’s hands. This segued into the set choreography performed by the company.

At a subsequent place in the piece, the participants re-entered, interacting with the dancers in “sharing a hurt” through movement, and at the conclusion of the piece the participants joined the company by mirroring the professional dancers’ movements of comforting each other and “opening their hearts.”

I am so grateful to Kezia for saving these notes as it gives a very clear example of how we integrated the community with the professional dancers for the actual performance of the Forgiveness Piece. I wish I had performance photos with community members but alas we don’t. I do have photographs from workshops.

In three of the four residencies, members of the community did perform with the dancers onstage as part of the piece, usually at similar places in the choreography but with different improvisations, based on what had been particularly meaningful to the workshop participants.

Once the structure for the community members’ improvisations was set, then the next stage was coaching. From Kezia’s notes:

Tucker coached the participants to refine their original movements to the highest possible level in terms of expressiveness, clarity of movement, dynamics, use of space and interaction with fellow dancers. With each urging, the participants’ movements improved, and their confidence grew, as evidenced by their lack of hesitation, the fullness of their movements, the development of their movements beyond the most obvious gestural representation of an idea, and the initiative they began to take . . . .

At all times, movement came from the participants themselves, as they continually re-examined their impressions of the forgiveness process. At one point, Tucker coached a participant moving from one place to another, “Transformation is not easy – it needs more tension,” and the participant reacted, “Right. I would have to WORK to get over there,” revising her movement accordingly. At another point, Tucker coached, “Make sure ‘transformation’ and ‘letting go’ are not the same.” The participant appealed, “Help me,” to which Tucker responded, “It has to come from you. Let your energy change.’’ It did, with a visibly expanded movement.

In one-and-a-half hours, the participants had been incorporated into the piece with movement both appropriate to their levels of technical ability and expressive of their individual explorations of forgiveness. The piece was performed with unified commitment and fluidity, and extremely well received by the congregation, many of whom noted the community participants with particular praise.

The time in Delaware continued with different community members joining the company when the Forgiveness Piece was performed at SAMS.

The first residency indicated that what we planned was indeed working. If community members participated in a workshop earlier in the week then it was no problem to include them in the performance piece. Since Kezia was there as an evaluator for the grant she asked participants for feedback about effectiveness of the workshops. Here are comments from two of the participants.

Participant 1: “I’m usually intellectual, and movement is not. In the workshop, I chose to explore my relationship with my daughter, and I discovered how angry I really was – I didn’t realize until I moved that it was anger I was feeling.”

Participant 2: “JoAnne had us do a movement exercise about sharing a hurt – it really lessened the hurt!”

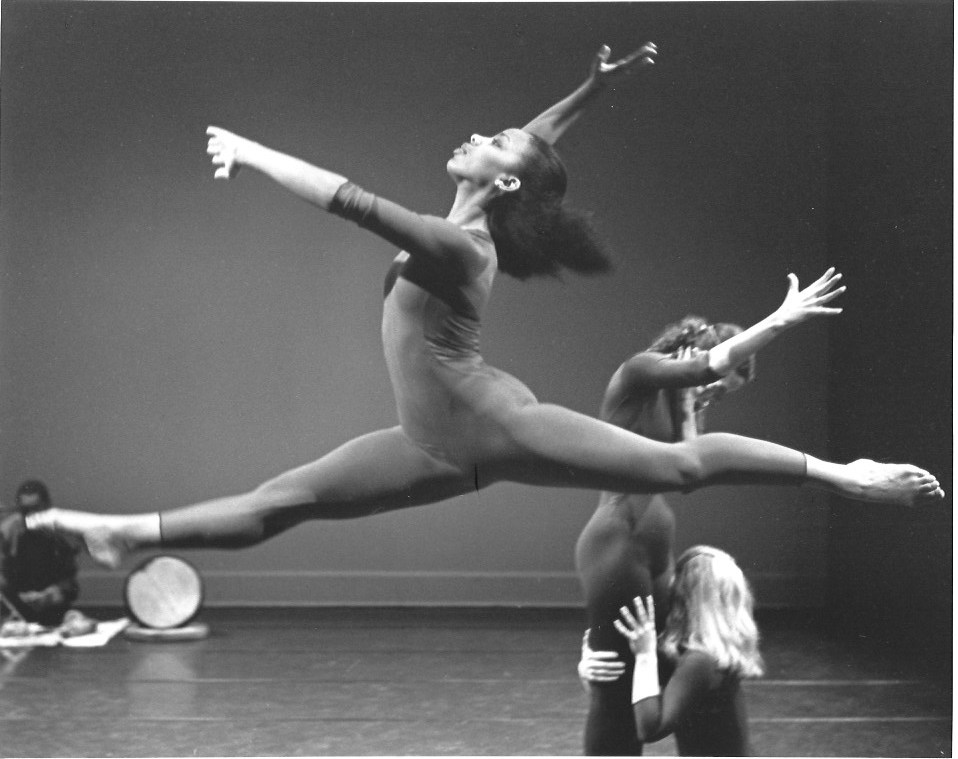

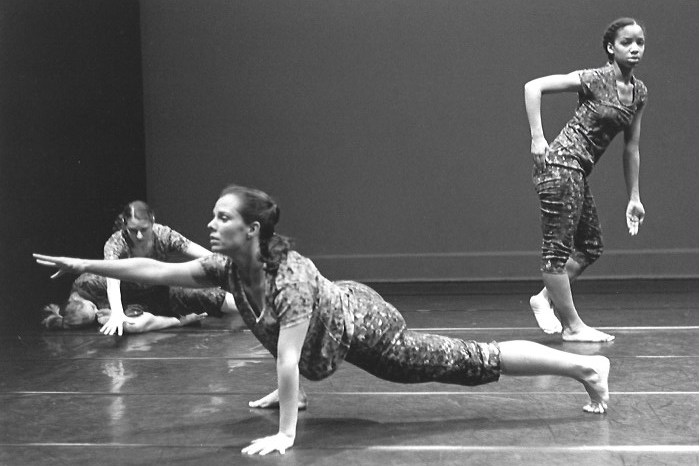

Our second residency began just a little over a week later at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institution of Religion in New York City. Workshops were very similar and participants included both rabbinic and cantorial students of HUC-JIR and people living in the neighborhood. I am delighted that we have some pictures from these workshops which were held in the very beautiful HUC-JIR chapel, a place we were very familiar with, as that was our home performing space.

to join the company in performance

to join the company in performance

[print_link]