That is the question coming to mind for me right now. By “home,” I mean my spiritual home. There have been times in my life when I have experienced transcendence, by which I mean losing my sense of self, and becoming one with the moment and people I am interacting with, so that the moment exceeds the ordinary.

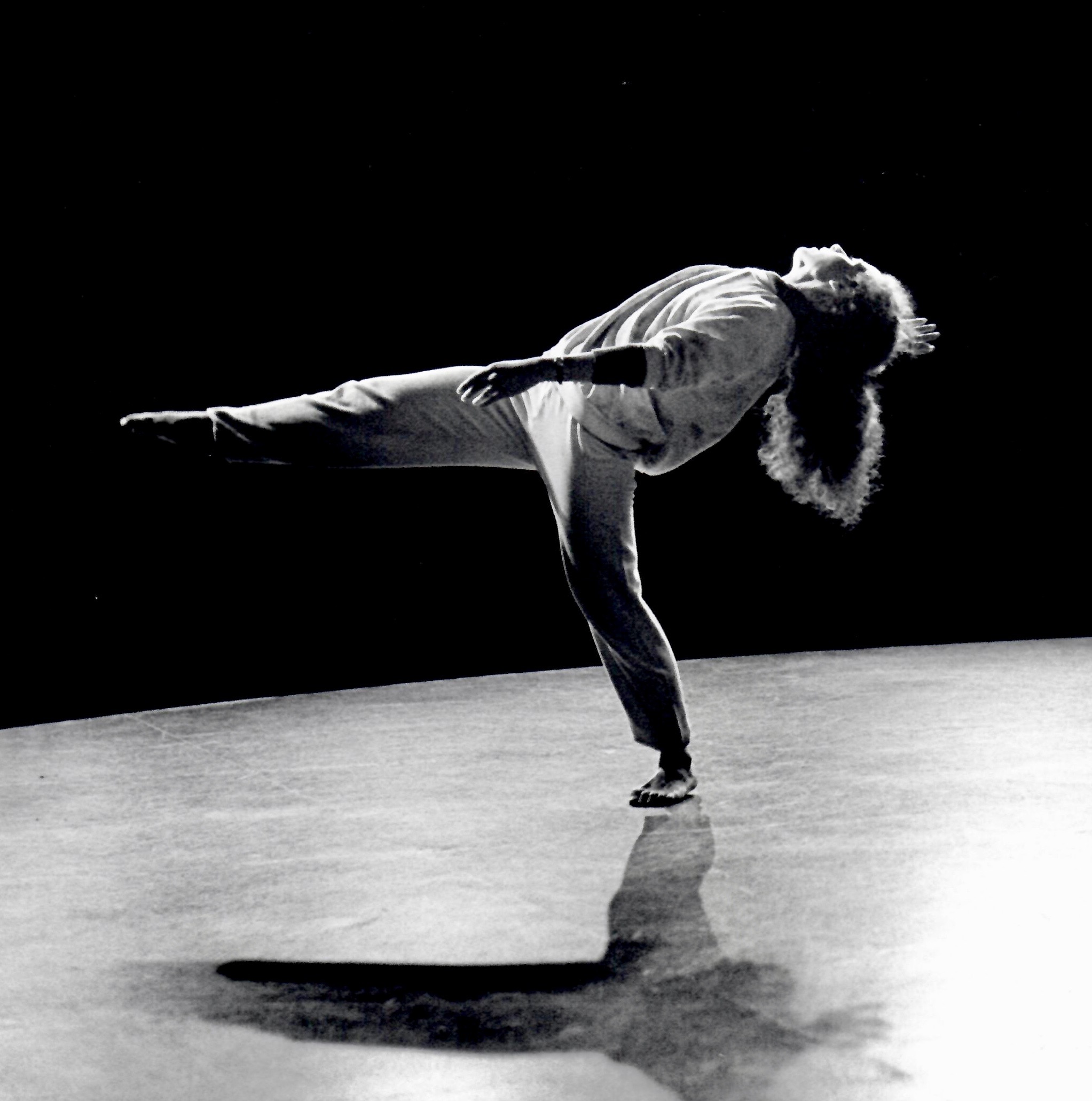

This has happened to me when I have been dancing or improvising, mainly dancing as part of liturgy or in an improvisation based on a Torah portion. And it hasn’t happened very often. It has also occasionally happened with a simple improvisational exercise like mirroring when the person whom I am partnering and I become one.

When I was performing, it happened only after I really knew the choreography so well that I didn’t need to think about the movement or the space I was in. I remember a performance one Sunday morning at Rodef Shalom in Pittsburgh where I had been coached by a good friend and fellow dancer, Lynne Wimmer. We were to be part of the morning service, integrating our piece of In Praise into the liturgy. I had a short solo, following the silent prayer, to the liturgy “May the Words of my Mouth.” Lynne had coached me to fully use my hands in each movement phrase and as I reached out in a circle to the congregation. This was an opportunity to take everyone in and reach to the back row. That morning my performance transcended how I usually did the piece, and at the same moment, the sun poured in through the stained glass windows.

As director of the company, I often saw when a dancer knew a particular solo or piece of choreography so well that they became one with the moment. That was a joy to watch, and I felt my energy totally with them.

On one occasion, the transcendence happened when I was leading a Doctor of Ministry Class at Hebrew Union College and we were dancing a line of text from the Torah. I don’t remember the line of text, and in a way it wasn’t important. It was the second class of a 12-week course, and I had decided to introduce the group to improvisational movement. None of the participants were dancers. They were rabbis and ministers, open to experiencing something new but not totally sure about dance. We began and continued for about 20 minutes without saying anything, sometimes moving alone, sometimes with one other person or with three or four people. There was no music. We were focused and intent on interpreting the line of text and interacting with each other. At some point which seemed right, I said, “Let’s bring it to a close.” We did, and then quietly sat down. No one spoke for a long time. I didn’t want to break the silence. We all knew we had become a total group together and that a spiritual experience had been had by all. Slowly people began to express their feelings. I finally ended by saying that in the second class they had gone beyond my purpose in teaching the entire course.

As time progressed, as director of the dance company which was very much rooted in the Jewish tradition, I found that my original reasons for starting the company were fading. My first reason had been that the prayers (particularly in the English translation) were difficult for me. I knew that they had been around for a long time and felt that maybe if I studied them and used dance to interpret them, I would find their meaning. In a way that did happen in the creative process when I and whomever I was collaborating with brought ourselves to the prayer. And some of the songs that had been written for the prayers stimulated and inspired movement. Not understanding Hebrew was a plus. The original language seemed to fit the prayer, but for me, when the prayer was translated into English, that was where I had a problem and definitely still do.

The other main reason for starting the company had been to see if I could find the woman’s voice, particularly in the Torah. So for years I did what in the Jewish tradition is called creating “midrash.”

Midrash is an interpretive act, seeking the answers to religious questions (both practical and theological by plumbing the meaning of Torah……Midrash responds to contemporary problems and crafts new stories, making connections between new Jewish realities and the unchanging biblical text. https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/midrash-101/

I explored text, using dance to create midrash, seeking the woman’s voice in that text. While it was great fun exploring in this way, and eventually co-authoring a book called Torah in Motion: Creating Dance Midrash, I began to feel more and more disappointed and discouraged to realize how patriarchal the Torah and prayers were, and I wasn’t satisfied with just adding a female biblical name to a prayer or creating a midrash on Sarah. I learned from a rabbi friend of mine that in the 1970’s when the women’s movement in religion began in earnest, some women explored midrash and others found they needed a whole new study. I realized I was now at the point of needing a new story.

When 9/11 happened in NYC, I lived just across the river, and the towers were part of my neighborhood. I was deeply affected by the event. A few weeks later a friend took me to hear Thich Nhat Hanh at Riverside Church. I was fascinated. Here was a different way to look at your enemies. During the fall, Sharon Saltzman, Joseph Goldstein and Sylvia Boorstein all offered workshops in NYC. I liked what I was hearing and began a meditation practice. I also liked the emphasis of sending wishes of kindness to all people – whether your family, or the person you have the most difficulty with– or as Thich Nhat Hahn would say, “giving your enemy a gift.” It became increasingly hard for me to say the prayer for peace in Israel as there was no extension to wish for peace for all (non-terrorist) people. I continue to be troubled by this. Yes, I very much want peace in Israel and will pray for it; however I also will pray for peace for the Palestinians. Real peace will only happen when both have peace and neither one has been conquered.

For nearly twenty years I have thought of myself as a BuJew (Buddhist/Jew). I went regularly to dharma talks and often weekend retreats at Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe. I continued my meditation practice. During COVID I even increased my meditative practice, thrilled with all that was available online, especially at Upaya. I was fascinated with The Hidden Lamp, “a collection of one hundred koans and stories of Buddhist women from the time of Buddha to the present day.”

This revolutionary book brings together many teaching stories that were hidden for centuries, unknown until this volume. These stories are extraordinary expressions of freedom and fearlessness, relevant for men and women of any time or place. In these pages we meet nuns, laywomen practicing with their families, famous teachers honored by emperors, and old women selling tea on the side of the road.

Each story is accompanied by a reflection by a contemporary woman teacher—personal responses that help bring the old stories alive for readers today—and concluded by a final meditation for the reader, a question from the editors meant to spark further rumination and inquiry. https://wisdomexperience.org/product/hidden-lamp/

I even began attending special workshops led by Sensei Zenshin Florence Caplow, happening nine or ten times a year, that looked at a different story each time and then encouraged us to write, based on key words that stood out to us. I did that for two years, and then one time while doing it I had an aha moment: in a way, I was doing midrash on another patriarchal religion.

I felt sad and a bit lost again. This was not my story either. I continued my meditation practice but I found myself less motivated to attend dharma talks. I still held onto much of the philosophy of loving kindness, mindfulness, and offering prayer to all people.

Then this High Holiday season, I streamed services from Central Synagogue in NYC. I had streamed them before and liked them. This year was different. I had lost over 30 lbs. and could move/dance again and so I found myself inspired by quite a few of the traditional melodies like Hashivenu and V’al Kulam. These were prayers I had previously choreographed, and since I was at home alone, I got up and danced. A feeling I hadn’t experienced for years returned. A spiritual high. Central’s service is filled with the most amazing music. Led by Angela Buchdahl, who is ordained as both a rabbi and a cantor, the services incorporate an outstanding selection of music, and even if I still have problems with the prayers in English, the music takes me to a spiritual place I haven’t been for a long time. The sermons by all Central’s rabbis are thoughtful, and the congregation is involved in social action – even a prison project.

During COVID, Central Synagogue streamed and was excellent at building a large online following. They then formalized the online streaming with a program they call The Neighborhood (I thought of Mr. Rogers and his neighborhood when I first heard its name), where people can join and participate in additional programs via Zoom. I surprised myself and joined right after the Yom Kippur service. So, the question I opened with… can one go home again? I think so, with a new awareness. My thoughts are I am the person who brings mindfulness and meditation from a twenty-plus-year regular practice, to find transcendence in dance by becoming the prayer or text rooted in my Jewish tradition.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Print This Post

Print This Post